Behind an inconspicuous flyer, a single photo or the floor plan of a flat, there can lay entire biographies. What do these objects tell us about queer life in Munich? As part of the "Archives in Residence" series, the Archiv Galerie at Haus der Kunst presents numerous documents from Munich's queer history and culture. Sabine Holm, Christine Schäfer and Thomas Niederbühl share their personal memories, which they associate with the exhibition objects.

Sabine Holm on the founding of "Lillemor's Frauenbuchladen"

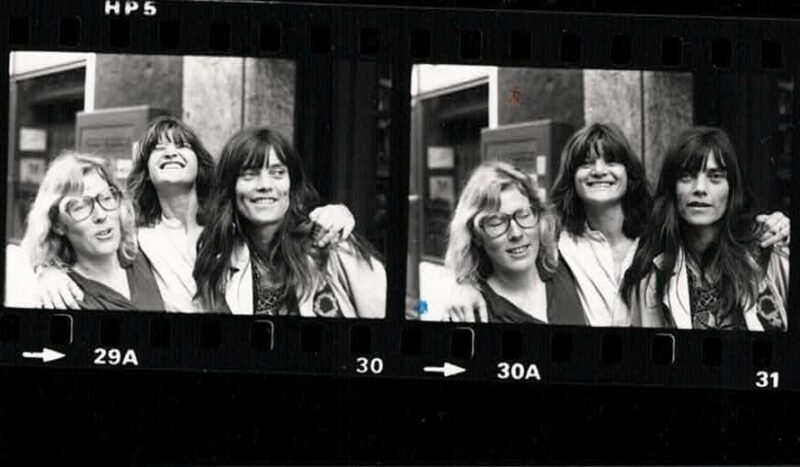

I don't recognize the two women in the photograph who have settled down in the middle of the bookshelves, but the image is a good depiction of what we were about. It must have been taken in the very early days, in 1975, shortly after the opening of "Lillemor's Frauenbuchladen". On the one hand, we had clear ideas and intentions; yet, at the same time, we were naive and had idealistic ideas about all the things the bookstore should be. But one intention was clear: it should be both a meeting place for women and a professionally run bookstore for feminist literature. I had previously worked as a bookseller in a publishing house. As a feminist, I wanted to create a place for literature by and for women. We also wanted to create workplaces that were adapted to the needs and realities of women's lives. Such things included family-friendly working hours, opportunities for leadership positions and a violence-free environment. We felt increasingly responsible for our female customers and quickly began to carry out social and advisory activities. All this initially overwhelmed us. We were primarily concerned with literature, and—in the 1970s—when we came up with the idea of establishing a women's bookstore, literature was firmly in male hands: literature was thought, written, published, evaluated, and prizes awarded from a male perspective.

It was clear to me that we would encounter resistance. Why? Because, back then, there were so few women in influential positions who were assertive and self-confident, i.e., so-called "exceptional women". This meant that the problem of the unequal distribution of power between men and women could be considered solved. The comedian Carolin Kebebus recently summed this phenomenon up with the comment, "We already have a woman." This attitude was also reflected in the context of literature. Christa Reinig, for example, was a well-known Munich author. She was famous and recognized in the literary world because — and here comes a questionable compliment — she could write like a man.

As the photograph shows, we opened with very few books on our shelves. There wasn't much feminist literature around yet. It was only then that we realized we were filling a void. In addition to a classic bookstore assortment of fiction, Kaschnitz, Bachmann, Aichinger, etc., we wanted to include space for magazines and books that had just been published in Germany, such as Shedding and Literally Dreaming by Verena Stefan and Der kleine Unterschied by Alice Schwarzer; every day there was more feminist literature available. We also sold children's books, crime novels, etc. Over the years there was also more and more lesbian literature, such as Rita Mae Brown's Rubyfruit Jungle and American manifestos like Lesbian Nation.

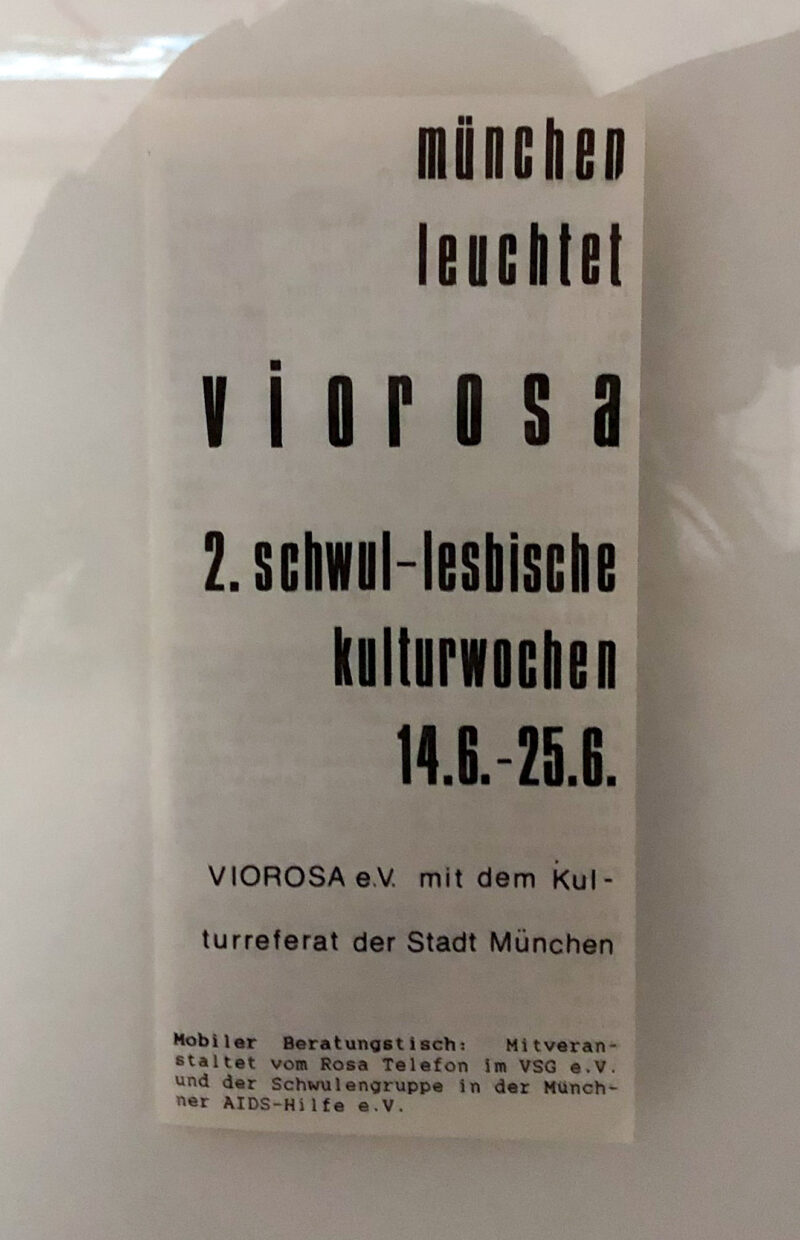

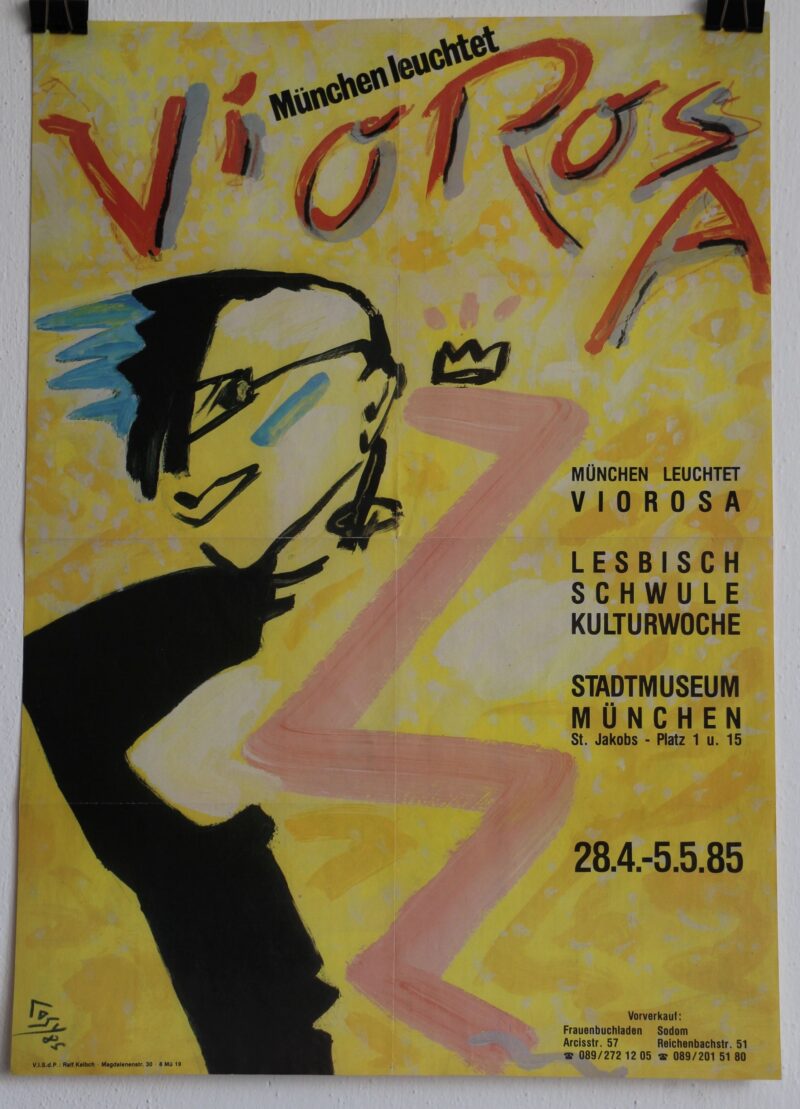

Thomas Niederbühl on the political movement "VioRosa"

At first glance, the pamphlet "München leuchtet VioRosa 2. schwul-lesbische Kulturwochen" (Munich Shines VioRosa. The Second Gay-lesbian Cultural Weeks), which is on view in a display case of the Archiv Galerie, appears utterly inconspicuous. Yet, concealed behind the 1989 "VioRosa cultural weeks" are historically notable events for both Munich’s queer community and my own biography. When opened, the leaflet reveals an extensive cultural program consisting of film screenings, discussions and cabaret and theater performances. The CSD Parade (Christopher Street Day or Munich Pride), attended by six hundred people, marked the conclusion of the cultural weeks on 24 June 1989. Today, the CSD brings tens of thousands onto the streets. In the 1980s, I was very active in the gay movement as well as in "VioRosa", which was first held in 1985 at the City Museum. The second edition of "VioRosa", to which the leaflet in the display case belongs, took place in 1989 in the so-called "Loft", an old factory building behind the Ostbahnhof, which was available for temporary use. The name "VioRosa" unites two groups: Violet stands for the feminist lesbians and pink for the gay activists. At the time, cooperation between lesbians and gays was not a given, as gay men often appropriated and patronized lesbians, who therefore preferred to engage and collaborate with feminist women. Yet, I was part of a new generation of gays and lesbians who were saying, "Despite all the differences in our desires and our social environments, we're discriminated against equally, and we want more visibility, more participation and more acceptance beyond our own subculture." "VioRosa" was only possible thanks to a contribution of 25,000 German marks from Munich’s Department of Culture. However, this funding led to protests from the CSU (Christian Social Union party), which immediately asked if the money would not be better spent on children's theater.

Following the appearance of press reports about "VioRosa", the Catholic Church revoked my teaching license, and I could no longer become a religion teacher, essentially banning me from the profession. In the context of "VioRosa", the first gay local politician, Gerd Wolter of the Green Party, suggested—after quitting the city council—that we gays establish our own voter initiative. We were skeptical at first, thinking along the lines that we would be creating a quasi-Gerd Wolter rescue club. On the other hand—and this is what convinced us to create the initiative— the AIDS crisis in the eighties was threatening gay and lesbian community. This threat came not only from the mass deaths of gays, but also from the culture wars between gays and the CSU Free State, which relied on coercion and exclusion instead of enlightenment and self-determination as we did. We were also tired of constantly stepping on the toes of politicians from outside the gay community. So, the following September, we founded the gay-lesbian voter initiative "Rosa Liste" (Pink List). In October as a 28-year-old student, I was nominated as the initiative’s top candidate. Since 1996 I have served on the city council, elected five times for six years (1996, 2002, 2008,2014,2020), most recently for the 2020 to 2026 term.

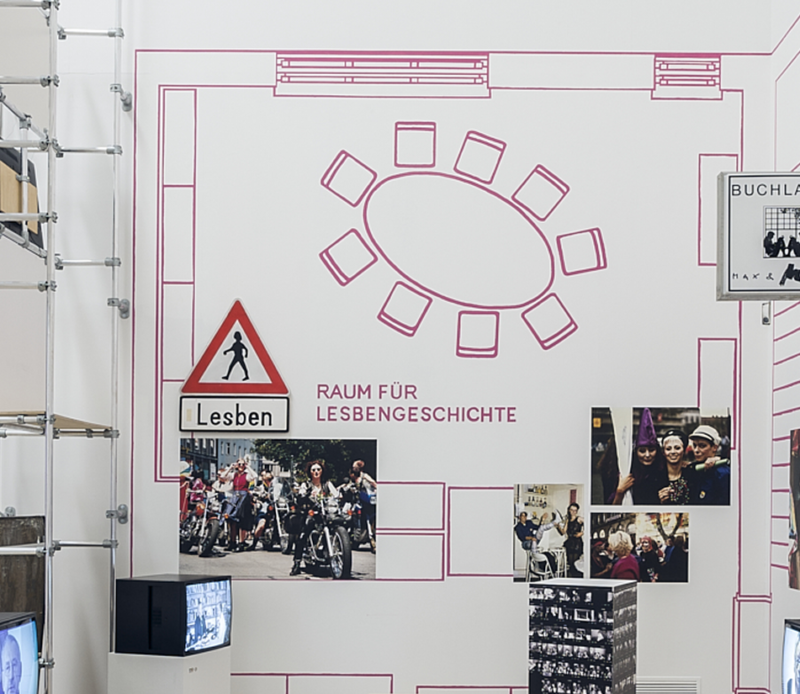

Christine Schäfer on the "Room for Lesbian History"

I am pleased that—with the establishment of the Lesbenarchiv (Lesbian Archive)—this special focus of the "Forum Queeres Archive München e.V." has gained prominence in the exhibition.

The Forum was originally an archive for gay culture, and some time passed before lesbians became more visible and assumed their place in the association. In the early days, the Forum was located at Müllerstraße 43a from about 2000 to 2005. The space included an office, an archive room and an event space. It took fourteen years before—at my instigation—we received funding from the city in 2014 for a place to preserve archives related to lesbian culture at Bayerstraße 77a. I joined the association in 2000, one year after its founding. I recognized the dearth of archival material and documents relating to lesbians. At the time, I was writing a non-fiction book entitled Nachkriegsfrust und Aufbruchslust. Lesbisches Leben in München in den 1950er bis 1970er Jahren. Sieben Biografien (Between Post-war Frustration and Aspiration. Lesbian Life in Munich from the 1950s to the 1970s. Seven Biographies), for which I had interviewed women in their thirties and forties. My goal was to show what it then meant to be a lesbian, to have a coming-out and what significance the women's movement had. In the process, I realized repeatedly that there was a lack of documents and records related to such themes, and that—in fact—there was extraordinarily little lesbian documentation at all. Through my work in the Forum, as well as events like the Lesbian Spring Meeting, lesbians learned about our activities and began to share their personal photographs, objects, documents and posters with us.

The Lesbenarchiv is housed within the Forum in a separate room we call the "Room for Lesbian History", which contains a display cabinet, the inventory of which reflects a chronicle of events related to LGB history. "LeTRa," for example, donated its files to the archive. Other displayed objects—such as buttons, mugs and other ordinary items—constitute important testaments to our past. The presentation also includes information about certain movements, such as the "Women's Resistance Camp", a women's camp, which was active in the eighties to early nineties and founded in reaction to nuclear armament here in Germany. When men talk about peace, it has a different connotation from when women talk about peace. There was a slogan saying as much: "What man calls peace is daily war for women."