Text and language are constant elements in Sung Tieu’s artistic practice. The interplay of autobiographical events, current political events and pure fiction gives rise to her extraordinary text work currently on display at the Haus der Kunst as "Sung Tieu. Zugzwang."

Tieu, who was born in Hai Duong, Vietnam in 1987 and lives in Berlin and London, uses the form of newspaper articles and news items to write fiction. Often, it is based on archive material and documents that are subtly woven into the multi-layered narratives of her multimedia installations.

With Zugzwang (2020), Tieu has developed an imposing, claustrophobic architecture in the form of an office environment for the South Gallery at the Haus der Kunst. Topics such as (European) migration politics and the structures of power inherent in bureaucratic state apparatuses are addressed not only through sound and sculpture work, but through fictional newspaper articles and an in-depth study of modified asylum and immigration applications addressed to authorities.

Chess or the Construction of Identity in Bureaucratic Processes

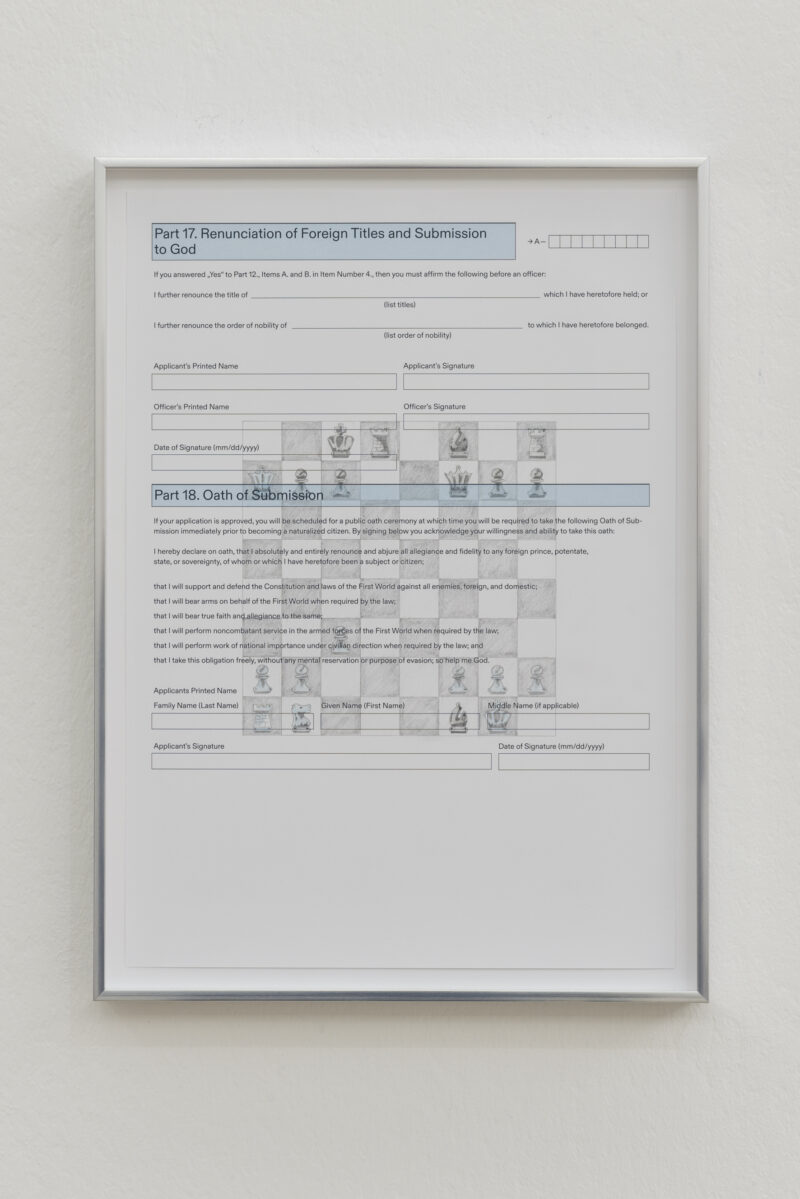

Hanging on the walls of the gallery, the 31 A4 documents in their plain aluminium frames appear innocent: a ten-page application for asylum, a registration form granting the right to stay, a twenty-page citizenship application. For the expansive Alekhine’s Defence (2020), Tieu didn’t just hang up the documents on the wall as a readymade, but edited them beforehand. She changed the fonts of the questions to her own design, and removed all references to specific states so the administrative forms could come from any country. Using fine pencil lines, she has drawn a chess board replete with pieces on every document. Reading them from left to right, move by move, they turn into a complete chess game.

For the most part, Tieu has taken the questions from actual applications and only changed them minimally. However, where exactly the artist has intervened is not disclosed. The intimate biographical details that these documents ask for, as well as the (lack of) space given for certain answers, showcase the influence the bureaucratic state apparatus has on the applying individuals.

“It is a system of classification and identification that almost always anticipates the answer”, says Tieu in an interview with Cédric Fauq and Damian Lentini published in the catalog accompanying the exhibition. For her, bureaucracy is “a faceless tyrant forcing you to fill in specific information without the possibility to engage in a critical dialogue or ask questions yourself.” When filling out these documents, the applicants are faced with the task of strategically presenting their individual experiences and biographical details in such a way that they comply with the standardised requirements of the nation state: Which part of my history do I highlight when I apply for asylum in a country? Which part do I hide, so it isn’t to my detriment? Which position do I take on to reach my goal?

Here, performative aspects of language become clear; in line with J.L. Austin’s theories on the philosophy of language in the lecture series delivered at Harvard University in 1955, entitled How to do things with words (see J.L. Austin: How to Do Things with Words: The William James Lectures delivered in Havard University in 1955, Oxford, 1973). He argued that spoken words can also be acts, and that in addition to constative, there are performative utterances. Through such ritualized speech acts, for instance, a registrar saying “I now declare you husband and wife”, a fact is spoken into existence that is then affirmed by signing an official document. Thus, performative speech acts constitute reality, as they are effectively creating social, economic and judicial facts,as Erika Fischer-Lichte describes in Ästhetik des Performativen (Frankfurt am Main, 1996, p. 31) in reference to Austin. Tieu’s Alekhine’s Defence powerfully shows this: The things we fill in a document or we tell civil servants become part of our ever re-constituting identity. At the same time, these documents are trying to restrict our agency by asking questions suggestively or leaving only limited boxes to tick, and are thus actively impacting our answers.

Additionally, the documents draw attention to the exclusionary practices of race-based othering in bureaucratic processes, through which social inequalities are reproduced through alleged differences in order to keep existing structures of power intact. Because of this, the knowledge that serves as the basis of these forms is only objective in theory: through rules of law, bureaucracy attempts to objectivise processes of gaining access, as well as the decision about these, which at their core are nonetheless highly individual and subjective. As part of the development of Zugzwang, Tieu has engaged with anthropological studies on formal applications for asylum. The artistic realization of her research findings shows in rather unique ways that there are only losers in this powerful game of horizons of expectations and fictions of identity: in her drawings, Tieu references a tournament game of chess between Agustin Freyria and Carlos Torre Repetto in Mexico City in 1926. Torre Repetto, who as a child had emigrated from Mexico to the US in 1915, won the game and with it the Mexican championship title. Yet his triumph wouldn’t last long: the same year, he was forced to forever abandon his chess career following a nervous breakdown. Allegedly Torre Repetto suffered the aforesaid nervous breackdown when he was just denied a preaviously promised lectureship at the National University of Mexico while receiving a message by his fiance that she had married somone else, as David Hopper and Kenneth Whyld mention in The Oxford Companion to Chess (London and New York, 1992, p. 425).

Chess is also the origin of the work’s title: Alekhine’s Defence is one of the openings of a chess game that wants to bring the king in a secure position, named after chess world champion Alexander Alekhine. Torre Repetto used this tactical move in his game with Freyria, which ultimately led to his win. Tieu’s art connects this strategy of defence with that of the bureaucratic state apparatus and shows how it “defends” itself against too many asylum seekers. “Zugzwang” equally describes a move in a chess game by which the player has to move one of their pieces in a position that is to their own detriment. Asylum seekers, or rather all people who are at the bureaucratic apparatus’ will, see themselves repeatedly confronted with such a detrimental position. As Tieu says, “It’s as if you are entering a game already wounded.”

Autofiction in Newspaper Format

The interwovenness of reality and fiction comes up again in other text-based works that are part of Zugzwang; rather inconspicuously, three fictional newspaper articles are placed on one of the shelves, the magnetic board and the desk. Manning the Deck, Citizen of Nowhere, and Borders 2.0 (all from 2020), are a continuation of Tieu’s series Newspaper 1969–ongoing.

In previous exhibitions such as Loveless (2019) or Parkstück (2019), Tieu has already placed newspaper articles she wrote next to drink and food packaging on prison furniture and so, almost casually, integrated her text-based work with her sculpture work, just as she does in Zugzwang.

It appears as if someone has just sat at the desk and read, left the newspaper articles on the shelf by coincidence (and yet in perfect view to be read by the audience), or stuck them on the magnet board a long time ago and perhaps already forgotten about them. Because of this feigned casualness they fit in perfectly with the spatial narrative, while also pointing beyond the museum space. The stories are a window to the outside world and expand the exhibition space via this fictional narrative by another level of thought.

Tieu’s articles tell a story of migration, marginalisation, bureaucratic power and cultural identity. Manning the Deck, for instance, is about Mr. Stevens, who shortly before his retirement was working on the Dublin II Regulation as a government officer in Brussels, and had always followed the rules of his employer unquestioningly. The character of Mr. Stevens is borrowed from the protagonist of the same name in The Remains of the Day (1989) by Kazuo Ishiguro. The article Citizens of Nowhere deals with a well-to-do multinational married couple whose daughter lives in London and becomes stateless because of a magisterial mistake. The third article, titled Borders 2.0, focuses on the increasing use of allegedly neutral technologies in the asylum process.

Tieu’s references to her own biography become clear in these newspaper articles. The earlier article Inside the Block (2019) tells the story of life in a housing facility for asylum seekers in Berlin Hohenschönhausen, growing up in the Vietnamese diaspora in the former East Berlin of the 1990s, as well as Tieu’s quasi-nomadic life between Berlin and London. It does so not only through photos and other memorabilia, but also on the textual level and thus integrates it into the overarching narrative of the exhibition. The newspaper articles are hence never complete fiction, but cleverly spin current political events, fiction and autobiographical fact into an individual history. The Vietnamese filmmaker and theorist Trinh T. Minh-ha describes this practice of interweaving fact and fiction under the title A sketched window on the world in her monograph Woman, Native, Other (1989):

It is said that the writer’s choice is always a two-way choice. Whether one assumes it clear-sightedly or not, by writing one situates oneself vis-á-vis both society and the nature of literature, that is to say, the tools of creation. […] Neither entirely personal, nor purely historical, a mode of writing is in itself a function. An act of historical solidarity, it denotes, in addition to the writer’s personal standpoint and intention, a relationship between creation and society. (Trinh T. Minh-ha: Woman, Native, Other. Writing Postcoloniality and Feminism, 1989, p. 20)

Tieu herself calls this process “autofiction”, a term that has been established in contemporary literature as well as art. It describes “a technique to use the self as a mirror, that projects back the thought process about the most private and emotional aspects of one’s own life onto the outside world that has shaped this very self”, as the editors of Texte zur Kunst argue in their foreword to the volume Literatur (Texte zur Kunst, vol. 115, 09/2019, p. 6) Tieu’s language-based work, as well as her stainless steel sculptures with their mirroring surfaces, continuously encourage (self)-reflection. They make obvious that the knowledge of migrants and post-migrants is needed to question the points of view and modes of engagement of pluralistic societies, and challenge assumed truths about “us” and “them”. The overarching autofictional narrative of the exhibit thus turns into a tool to highlight societal inequities and confront them with alternative histories and forms of knowledge.

Lisa Paland is an art and cultural studies scholar and works as a curatorial assistant at Haus der Kunst.