Shortened version. The full text can be found in the exhibition catalog.

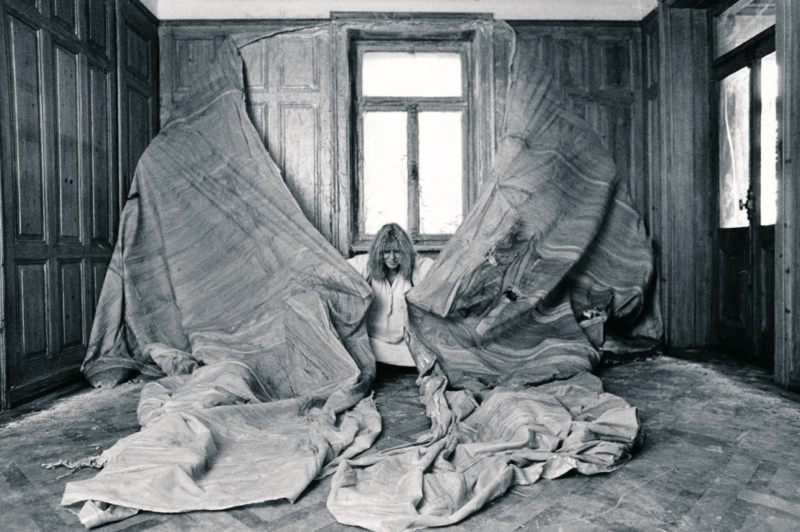

Wrapped in a white robe, Heidi Bucher’s body is in a state of intense physical tension during the skinning of the walls, carried out in her father’s former “Herrenzimmer” in the abandoned upper-middle-class parental home in Winterthur (1978; fig. 1). In the various photographs and films of her historical skinning, the material abundance of the latex imprints peeled from the walls envelop Bucher like the wings of a dragonfly rising above its own past. In her manifesto “Parkettlibelle” [Parquet Dragonfly], Bucher described her artistic work as a “process of metamorphosis” in which the disentanglement from social conditioning is accompanied by a softening and mobilisation of objects – indeed static conditions. Bucher directed the gaze to the body in space, which is subjected to dynamic relationships and in which experiences, emotions and affects are inscribed.

Already manifested in her first skinning actions in the 1970s is Bucher’s future preoccupation with the human body and psyche in the context of private and public living spaces, and of social as well as gender norms and conditioning. Her main body of work began after she returned from several years of living with her family in Canada and the United States and her separation in 1973 from Carl Bucher. Approaching fifty at the time, Heidi Bucher turned from this point on to objects and places, from her own family history to begin with, the engineer’s family home.

The house as a place offering protection and orientation was at the same time defined by patriarchal structures, as can be traced in the gender-assigned areas of life and work. Women were systematically excluded from participation in public life by domestic and family obligations. The unrepeatability of the action, beyond its medial recording, led to an ostensibly permanent state – albeit one that is in fact ephemeral, given the material – in the form of ultimately transportable, space-filling installations comprised of latex skins, such as “Herrenzimmer” [Gentlemen’s Study; 1978; fig. 2]. With the detachment of the architecture from its original static context, the artistic action itself was also exhibited at the same time.

Prior to this, Bucher had already moved from the exterior to the interior at the place she named Borg, her studio in a former butcher’s shop on Weinbergstrasse in Zurich. There, at the entrance, she executed her first architectural latex skinning with “Borg” [1978; fig. 3]. She derived the name Borg from the German word “Ge-borgenheit” (safety, security); she thus created for herself a kind of personal shelter in which, between 1973 and 1978, an imagery for coming to terms with female oppression emerged in the form of the “Einbalsamierungen” (embalmings) and “Weichobjekte” (soft objects). Bucher arranged found textiles that had belonged to her family, for instance underwear, children’s and women’s clothes, or bedspreads, often covering them several times with layers of latex and adding motifs such as shells, a combination that at first glance seemed surreal. This was followed by the treatment of the latex surfaces with motherof- pearl, purple or gold pigments, which initially appeared to remove the works from reality, but instead ultimately opened up new spheres of interpretation.

At the time, Bucher also began to apply the signet of a fish to her objects – a deliberate allusion to the symbolic language of Paul Klee, who strongly inspired Bucher. The fish as a psychological and artistic symbol for dream interpretations indicate Bucher’s coming to terms with complex relationships that preoccupied her in dreams and fantasies and were also linked to childhood memories. Bucher commented on one of her key surreal works, “Anna Mannheimer mit Zielscheibe” [Anna Mannheimer with Target; 1975; fig. 4], which depicts a dress and a shell representing the head bedded on a duvet, as follows: “They are the Annas: me, my mother, my grandmother, all women. And they are called that because they had to survive in the homes of men.” The depersonalisation articulated in the clothing without a head refers to the omnipresence of the oppressive conditions that determined the lives of women and aims to visualise physically lived alienness. The soft objects carry hidden messages and convey various representations of what was experienced. Like a room or a house, the “Bett” [Bed; 1975; fig. 5] stands for a certain form of corporeality, a place where life is represented, from birth through the phases of illness up to death. It marks a zone of sexuality and the hidden, in that the private sphere separates itself from the public sphere. Bucher turned the bed into an object of public display which alternates between being a sculpture and a painting on the wall. Through her visual codes, she brought about a liberation of the subconscious – Bucher propagated the overcoming of gender roles.

Bucher’s knowledge of and appreciation for the avant-garde, whether it was Klee, Oppenheim or her teacher Johannes Itten, placed her in a line of tradition, but her advanced intermedial procedures and themes established her as a major representative of the international neo-avant-gardes in the context of the social changes of the post-war decades.

The idea of transformation was to reach a first climax in Bucher’s work with the draping of latex imprints of skinned walls into a wearable pearlescent body sculpture, “Libellenlust (Kostüm)” [Dragonfly Lust (Costume); 1976; fig. 6]. She wore the work performatively on various occasions, wrapping herself in the architectural shells that stripped away her former form and past in the process, as it were [fig. 7]. Bucher stated: “The metamorphosis is completed in the act of hatching, because it symbolises the breakthrough.” She appropriated a second body and used the covering to visualise social processes.

Louise Bourgeois made similar attempts to abolish dualistic gender identities with sculptural representations of fragmented body parts, for example by fusing male and female genitalia into bisexual symbols. Like Bucher, she experimented with latex early on in order to address sensitive relationships within the nuclear family and the associated feelings of fear and hatred. Through the unconscious and the personal, both Bourgeois and Bucher pushed forward to universal dimensions of heteronomy and humiliation of women in dominant family and social structures. Unimpressed by the heyday of modernism and the machismo of Abstract Expressionism in the New York art scene of the time, with which they were well acquainted, both artists devoted themselves to the ongoing demystification of female clichés with an open concept of work. By concentrating on fragmented and alienated organs, Bourgeois unleashed the body in art, but unlike Heidi Bucher, who was a generation younger, she ultimately remained bound to a binary gender order.

The lives of both artists and their late discovery by the art world once again illustrate the brutal mechanisms of women’s exclusion from the production of cultural relevance. Heidi Bucher’s first exhibition of latex works took place in 1977 at the Galerie Maeght in Zurich. This does seem to have been programmatic, if one also takes into account the invitation from director Elisabeth Kübler to Louise Bourgeois, whose work was shown there for the first time in Europe in 1985 with a survey exhibition. Kübler remembers that “being a woman” in the visual arts was a stigma at the time and that she could exhibit women artists only occasionally, in less busy times like the summer. The gallerist recently emphasised that both women knew how to avoid being categorised as feminists. Louise Bourgeois, who had not joined any activist initiatives, once remarked: “My feminism expresses itself in an intense interest in what women do.” In the same way, Bucher was also concerned in the 1970s with finding an identity beyond gender stereotypes by means of emancipatory strategies independent of men.

Feminist artists in the United States and Europe focused on the female anatomy. In Los Angeles, Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro founded the Womanhouse art installation as a project space in 1972 – in the context of their feminist art programme at the California Institute of the Arts – which served as a new protected sphere for women’s art production. Heidi Bucher was a supporting member of the Womanspace gallery and magazine and also participated in one exhibition. Without a doubt, the several years Heidi Bucher abroad, especially her time in Los Angeles, led to a personal and artistic emancipation that marked the beginning of her independent, main body of work from 1973 onwards. For she gained an artistic perspective that was very much sharpened by feminism – as is evident from the group of works titled “Weichobjekte” [Soft Objects]. From this point on, she focused on repressed spaces that eluded the public gaze but reflected the everyday reality of women – including those in her own family.

In 1978, the same year of Bucher’s first skinning of an entire room, namely her father’s gentlemen’s study, Bucher translated the article “Eva Hesse’s Sculpture: Mysterious Effects from Unexpected Materials” by the American art critic Barbara Rose, which dates from 1973 and which she had kept. The extraordinary importance of this archival material cannot be overestimated, as it conveys the high regard Bucher had for Eva Hesse’s work in distinction to Minimal Art. She must have been inspired by Hesse’s ambiguous treatment of the body and the organic qualities of her sculptures, which almost never slip into illustration. Associations with flesh and skin permeate Hesse’s work with natural rubber, fibreglass and polyester, which she used to create ephemeral sculptural formations. In doing so, she often made use of serial arrangements for her sculptures, which are never identical in form but nevertheless resemble each other. The sculptures, which are perceived as fluid and transparent in their spatial staging and fragility, thus differ greatly from the geometric rigour of the industrial materials of American Minimal Art. With “Contingent” (1969; fig. 8), the rolled-up clothing, mummified, so to speak, in fibreglass and latex, is an embodiment of disembodiment. Like entrails, the membrane-like textiles floating freely in space are exposed in their function as human surrogates.

With their artistic experimental working processes, both Bucher and Hesse tested the transformation of matter by means of natural rubber. Bucher picked up on the ambiguity of fluidity, for she was concerned with a radical departure from anonymous, commercial surfaces. She dealt with the transfer of psychic processes to the material, strove to make traces of personality visible and to work out a transitory character as a work process.

Already during her collaboration with Carl Bucher between 1969 and 1972 she transferred the sketches for static pictorial works borne by a futuristic belief in progress into performative objects alternating between costume and sculpture. An unmistakable Bauhaus-inspired interplay of fashion, design and architecture was palpable in them, which can be traced back to her training with Johannes Itten at the School of Applied Arts in Zurich. It is not surprising that this was followed by her own group of works, the “Bodyshells” (1972; fig. 9, 10) – wearable and danceable body sculptures reminiscent of organic sea creatures. She created symbols for the interplay of veiling and unveiling that celebrated a form of mutability in the sense of renewal.

In a written note, she named the earliest, three major skinnings of the Borg (1976), the parental home (1978) and finally the ancestral home (1980–82) – central places within her own biography – as the first productive phase after her return from the United States. From her very first architectural skinning, Bucher made sure that the work process was comprehensively documented photographically, and she also arranged for film recordings. In addition to the vast number of sketches and notes on these three specific projects, she henceforth also wrote courses of action. In these work instructions, she noted, among other things, the extent to which video recordings of the actions were essential. Later, she even formulated the wish that these should be exhibited in combination with the works. In her artistic concept, the subsequent comprehensibility of the actions by the viewers was thus anchored as a central concern. The video footage of various skinning actions from the 1970s and ’80s, recently rediscovered in the context of the retrospective at Haus der Kunst, shows Bucher making performative gestures and movements that seem to merge with the works and their surroundings. In these scenes, her body conveys an impression of a certain pictorial quality, which is due to the poses, in which she often intensely focuses on the imagined viewer. A direct relationship to the viewer was thus factored in, whereby her personal presence proves to be elementary.

During her first sojourn in New York between 1956 and 1958, Bucher became friends with the photographer Hans Namuth, whose photographs of Jackson Pollock’s painting processes were presented at The Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1967. It can be assumed that, in the mid-1950s, Bucher had already come into contact with this then novel, unusually dynamic reproduction of work processes. Interestingly, a short time later, sculpture was brought to life in the New York art scene by key figures influenced by avant-garde dance, such as Robert Morris and Bruce Nauman. Like Nauman, Bucher also explored inner and outer perception, reflecting on contradictions in the information provided by our senses. And like Nauman, Bucher was also interested in sharing private experiences of the body in the public space.

With the skinnings at the third site of her artistic explorations, the so-called “Ahnenhaus” [Ancestral Home; 1980–82; figs. 11, 13 ], which spanned two years, the conflict between the private and the public was to emerge as a seminal leitmotif of her work. In this ancestral home, the Obermühle in Winterthur, her grandparents once lived together with family members from several generations. In the use of the rooms of the centuries-old, historical building, the relationships between the members of the domestic community are revealed at the same time. Immanuel Kant’s moral philosophy (“The Metaphysics of Morals”, 1797), as well as the laws pertaining to marriage, parenthood and the head of the household emphasised by him, were reflected in the real conditions of the time in the form of a total abolition of liberties, in that people had to serve each other like personal possessions – especially on the basis of their sex. The effects of this repressive and static distribution of roles can be traced back in Bucher’s family through a great many personal fates over generations, as can the influence of social value systems through their transfer into the private sphere.

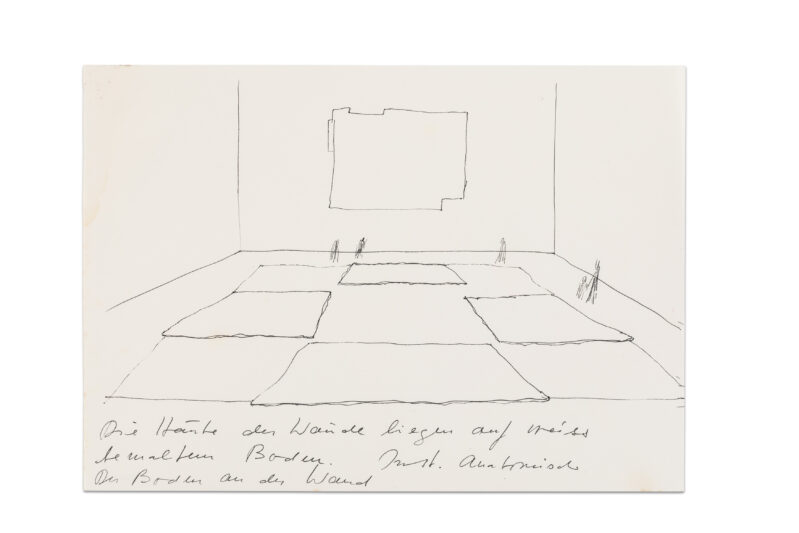

In her notes on this skinning project, Bucher made sketches of all the storeys and the floors, as well as their patterns, and noted the number of skinned floors, walls and windows. Traces of the historical surfaces of wooden and stone floors remained in the latex; Bucher therefore described the action as a “manifesto of the past”, whereby touching the house – fetching things over and stripping away what exists in our time – was her vision. At the same time, the floor skins from the ancestral home, reminiscent of oversized membranes, symbolised current body politics in that the respective space inscribed itself with its social definition and history into the material. Bucher aimed to counteract an alienation of the body and to make cultural codes visible.

A forgotten sketch has resurfaced in Bucher’s archive which includes a concept for a multi-tiered hanging of the floor skins from the ancestral home: on the floor, on the walls and free-floating in space (fig. 12) – a transfer of the sculpture in its singularity into a complex multipart and abstracted installation.

The prelude to a thematically new series of projects in the 1980s was to be the skinning action at the former women’s prison in Le Landeron, which emerged from Bucher’s participation in the 1ère Triennale Le Landeron “La femme et l’art” held there in 1983.

On the basis of her work instructions, it is possible to reconstruct the course of the skinning of the prison, which lasted several days and ultimately involved five performers whom she had previously invited in writing and asked to wear men’s underwear as well as bodices with long sleeves for the subsequent skinning of their own bodies. Video recordings by two camerawomen commissioned by Bucher herself, who filmed these skinning processes on 4 June 1983, have been found. The performers rubbed each other with milky rubber latex and, after the initial drying and rubbing of the suits with mother-of-pearl pigments, stripped off the skins – thus completing the “Schlüpfakte” [Hatching Acts]. The following day, the women clad in those body suits carried the room skinnings they had previously removed from the prison through the town to the town hall, where they finally – observed only by the cameras – symbolically performed their “Hatching Acts” again by undressing and leaving the room naked. Bucher defined this in writing as a performance, which she titled “Ablarven” [Unmasking; fig. 14]. The relationship between the action and its recording on film was based on the moment of community building and the physical experience shared with the onlookers. For Bucher, the presence of the artist’s body was indispensable, as those who witnessed the action would be able to relate to it with their own perception at a later point in time. In this way, she enabled a calculated, temporally unlimited reception of her works in the future.

Bucher commented on her participatory work as follows: “The hatching of the parquet dragonfly at Le Landeron prison is guaranteed by the process of shedding hard, solid, horrible, cruel things. The women have moved out of the larval shells and discarded them.” She had dedicated herself to the prison as the first of several social institutions where people are held against their will. She mobilised the history of these places to include women who until then had been forced to act as invisible subjects. Bucher demonstratively aimed at actively shaping the conditions, which she publicly displayed by means of a procession.

Only a few years later, in 1987, Bucher visited the abandoned Grand Hôtel Brissago on Lake Maggiore to carry out the skinning of the entrance portal (fig. 15). Built in 1904, the stately hotel served as a recreational retreat for European intellectuals and became a refuge for writers such as Thomas Mann and Kurt Tucholsky during the rise of fascism. When the Nazis seized power, what had once been a shelter of sorts became a state-organised “internment home” for Jewish children and women. Bucher confronted herself again with a building in which a brutal exercise of power over people had taken place, and the traumas experienced had caused both physical and psychological injuries. It was a place filled with collective guilt and sham, and with her skinning “Grande Albergo Brissago”, Bucher triggered memory processes and thus countered social repression and forgetting.

Hannah Arendt’s essay “We Refugees”, written in 1943 shortly after her arrival in the United States, was not translated into German until the mid-1980s, at roughly the same time that Bucher carried out the skinning in Brissago. In this essay, Arendt formulated the following regarding the silence about the Holocaust: “Besides, how often have we been told that nobody likes to listen to all that; hell is no longer a religious belief or a fantasy, but something as real as houses and stones and trees. Apparently, nobody wants to know that contemporary history has created a new kind of human beings – the kind that are put in concentration camps by their foes, and in internment camps by their friends.” With her artistic gesture, Bucher made a contribution to overcoming the post-war silence by means of remembering through action. She continued to use latex skins as surrogates for social body politics that represent mental processes of feelings, thoughts and memories.

That same year, 1988, Heidi Bucher sought out an abandoned private psychiatric clinic once run for several generations by the Binswanger family, the Bellevue Sanatorium in Bad Kreuzlingen, on Lake Constance. This was the culmination of Bucher’s preoccupation with body systems and their exploration in the context of psychological, social and cultural formation. The focus of her interest was the clarification of the medical experiments once conducted there to gain control over the minds and bodies of others who deviated from social norms and ideals. Bucher literally wrapped herself in the peeled-off latex skins, as can be seen in several film sequences.

The latex room imprint of the “Audienzzimmer des Dr. Binswanger” [Dr. Binswanger’s Parlour Room, 1988; figs. 16-18] has an intimidating aura, considering the scientification and pathologisation that the alleged hysteria patient, the later women’s rights activist Bertha Pappenheim, underwent there. Binswanger treated her in close exchange with his colleague Sigmund Freud, in whose study on hysteria Anna O. appears as the first test subject. Freud’s thinking about women was based on the conviction that the linking of biology and socialisation, of nature and history, shaped personality. “Anatomy is destiny”, Freud argued, which also extends to the clinical picture ascribed on the basis of gender. Such notions of natural conditions served throughout the twentieth century as legitimation for social realities and continue to do so, whereas Bucher positioned herself against this by exposing the body as a projection surface of social interests, as a carrier of heteronomies.

In feminism, social constructions of gender have been problematised time and again, be it Simone de Beauvoir’s exposing of the unequal treatment in patriarchy or Judith Butler’s expansion of the debate around polymorphous sexual identities. With her latex skinnings, Bucher ultimately offered an artistic blueprint for the abolition of the category of gender at a very early stage. Contrary to traditional concepts of the body, such as that of psychoanalysis she pleaded with her art for the abolition of attributions imposed on the genital zones. By contrast, focusing on the surface of the skin allows interpretations of body zones that are not reduced to sexuality – in much the same sense that Bucher understood psychic processes as a trigger of bodily sensations. With her radical notions of body and spatial transformations, Bucher’s work opened up an almost unlimited cosmos of possible new social designs. She breathed a narrative moment back into the works and liberated the body from subordination to the factual. Her interweaving of media resulted in a play with presence and absence – the body as the medium and focus of the transformation from nature to material and sculpture. Bucher’s oeuvre bears witness to the artistic discovery and emancipation of the sensual, sensitive body in the twentieth century, whereby she prepared the ground for genderless utopias with a processual understanding of the work and a radical understanding of material and positioned herself resolutely against rejection, oppression and discrimination.