In the early 1960s, the young painter Markus Lüpertz wanted to animate his paintings and set them in motion. He developed a serial painting approach that was heavily influenced by the films and cinema of his time. Pamela Kort's essay explores the beginnings of this form of painting.

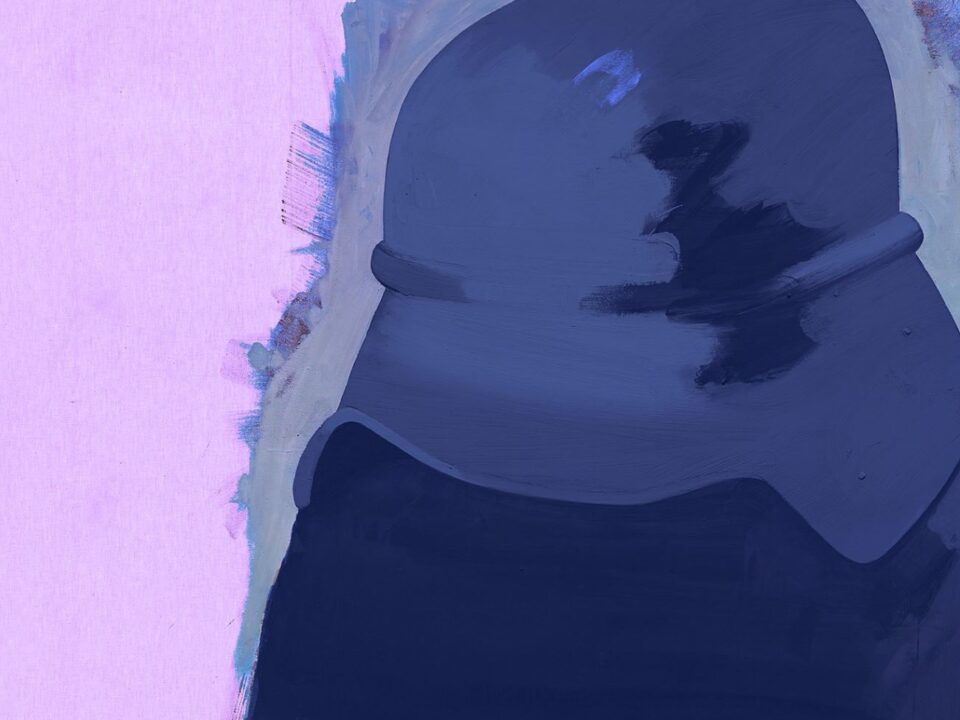

Markus Lüpertz’s Donald Duck paintings were the first large series of images he brought to canvas in the beginning of the 1960s. In the three works illustrated here, whose motifs are each different, Lüpertz began to explore the consequences of a discovery he had made while applying acid to film: that it might also be possible, in his view, “to bring paintings into motion.” Although comic books may have been the starting point for Lüpertz’s ruminations about the potential of the irreverent Disney character, animated films featuring Donald Duck also helped Lüpertz decide to use the motif to advance his own kind of abstraction. He surely realized that movies of all kinds hide disjunctions between space and time that are made evident by the gaps in the frames of comic-book images, known as their “gutters.” Moreover, animated films need not unfold chronologically nor tell any kind of story, as do comics. Lüpertz later would claim that what he wanted to achieve in these first paintings had more in common with the serial imagery of the flip-books (Daumenkino) that had preceded both comics and cartoons. That kind of “movie” appealed to Lüpertz because it animated images without recourse to a camera or animation stand, things that at the time were of little interest to him. Clearly it was the aspect of speed inherent to such pictures that also captivated him. That very quality—also a characteristic of Art Informel—would soon become one of the trademarks of his serial paintings, which he brought to canvas rapidly and simultaneously. Perhaps Lüpertz grasped as well that the Latin word anima means something that approximates soul and spirit. Animation thus implies the breathing of life into otherwise inert things. This would remain one of the primary aims of Lüpertz’s art.

He put it into words more than thirty years ago, stating: “The definition of my painting is to animate dead forms.” Siegfried Kracauer had long equated that quest with cinematic vision, writing in his 1960 book, Theory of Film: “We literally redeem this world from its dormant state, its state of virtual nonexistence, by endeavoring to experience it through the camera.” It was this point of view that led him to subtitle his volume The Redemption of Physical Reality. Although Lüpertz never picked up the book, that concept—that films can bring to life a “reality of another dimension”—was precisely what he sought to effectuate with his Donald Duck paintings and those that came after them.

Let us turn then to this first body of works to ascertain how their motifs function. To begin with, there is the artist’s designation of their almost abstract images as being Donald Duck. And yet far from a “representation” of that character, these paintings merely use his name to set into motion a process by which meaning is accrued, born from relational dissimilitude. Here, Donald Duck stands for a figure both known to a twentiethcentury public and something yet to be made visible, which it prefigures. For Lüpertz that thing was an achievement no less than the reinvigoration of painting, a heroic task given the denouncement of that art form during the 1960s as nearly exhausted of possibilities. Suspicious about the hype surrounding “avant-garde” art back in the early 1960s, Lüpertz also refused to buy into the gospel of the art world. Instead he sought a cipher with which to subtly critique it, one that stood for a different kind of sacredness. He found it in 1963 in the sidesplitting character of Donald Duck. Like Mickey Mouse, the miracles that his cinematic image could generate not only appeared capable of outdoing technological ones but could ridicule them as well. It was partly for that reason that those Disney figures had long since attained a kind of godlike status, and not just among children.

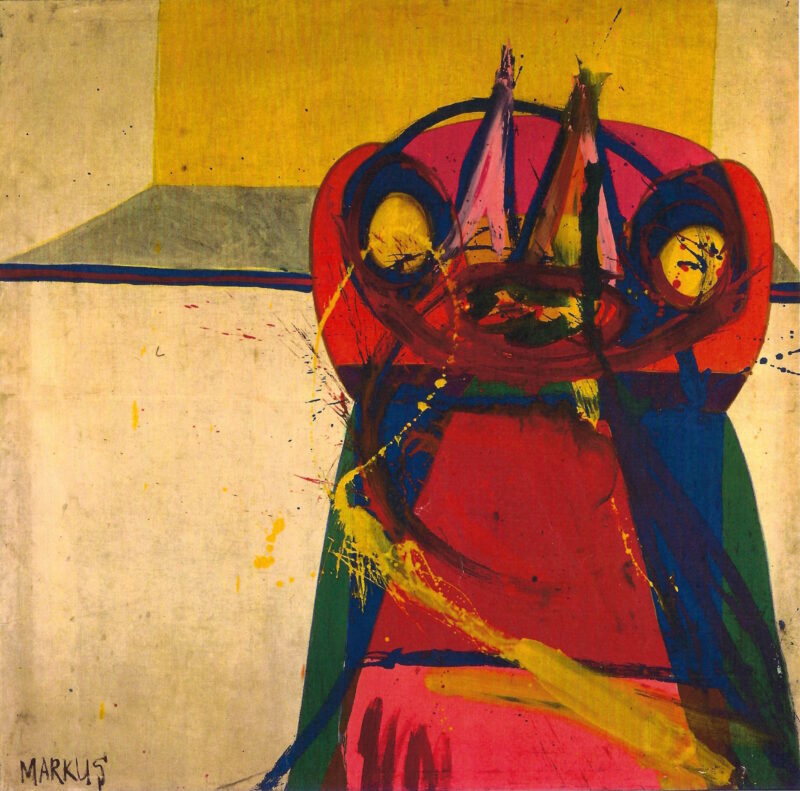

Abstracted almost to the point of non-recognizability, however, not much remains of the famous duck who is announced in the title of yet another of these paintings, Donald Ducks Heimkehr (Donald Duck’s Homecoming, 1963). All we can make out are his two wide-open eyes and the contours of what might be the bird’s bill. Standing directly before the viewer, in all its dazzling colors, this duck embodies Lüpertz’s aesthetic self, one also hell-bent on boundary crossing. A closer glance at Donald Ducks Heimkehr reveals that the bird has transgressed a border line as well. No longer confined to the virtual reality of film, he has stepped out of the luminous screen-like structure behind him and into the realm of the viewers, coming “home to them,” as it were. Lüpertz may have gotten that idea from a film as well: in Buster Keaton’s classic 1924 film Sherlock Jr., we see a projectionist who, after falling asleep during the showing of a movie, dreams that he can step into and out of its images at will. Lüpertz’s new propensity to abstract form also informed his handling of the 20th Century Fox logo, which launched the image. The logo seems to have burned itself into Lüpertz’s head, as would other cinematic motifs to come. Here it metamorphosed into fragments: the “20” split into two separate numbers, both of which became the zeroes of the figure’s eyes. The entablature below them became more pronounced, forming the bottom of the duck’s squared-off head. The edifice, which once held those numbers high, was transmuted into a body. Everything else has slipped away.

Lüpertz was drawn to the 20th Century Fox trademark in part because he appreciated its campy qualities. One need only imagine the scenario the artist experienced in the cinema time and again: the lights dimmed, then the curtain slowly opened, while gradually the screen lit up. Next came the 20th Century Fox studio’s vanity card, with its monumental letters set on a mammoth structure high in the sky, surrounded by beams of lights directed toward the heavens. Yet, back in 1963, Lüpertz did not make an pop icon out of the the 20th Century Fox trademark as for example artist Edward Ruscha did, but rather completely transfigured the trademark. He then deployed it in an effort to give a new twist to the two principal types of painting that in post-1945 Germany were held as next to godly right through the 1960s: the one of École de Paris and Informel aesthetics that had reached an apogee by then, and that of all the Pop Art makers whose work was then just beginning to overrun Berlin. Of the latter, it seems to have been Andy Warhol’s art that most challenged Lüpertz. His 32 Campbell’s Soup Cans (1961–1962) not only promoted that company’s logo but consisted of many nearly identical paintings. And then, of course, there were the films that Warhol began to make in 1963, Sleep among them. Word about them boomed across the Atlantic, soon reaching Germany. By using elements inherent to both styles of working rather than imitating them—swift gestural strokes of paint, an image from popular culture, a corporate trademark, and a serial approach to painting—Lüpertz attempted with his Donald Duck works to position himself as an artist within the arena of international painting. Quick on the uptake, Lüpertz began to see that through framing, rhythm, and repetition, films themselves sometimes create an atmosphere that evokes the presence of something “not of this world.” The same thing might be said about the enactment of religious rituals and the writing of poetry: all three practices set apart certain objects and epochs upheld as sacred. And so Lüpertz began to cast around for a term in keeping with that insight. It wasn’t long before he settled on the word Dithyramb. For Lüpertz, the dithyramb embodied “a poetic concept that led to Dionysus, meaning it included the heathen-hymnic and perhaps also was religious.” Dionysus was attractive to him as well because he was “the god of the exceptional.” He had long been considered a god of poetry and inspiration, but during the sixties a new concern with the condition of Dionysian ecstasy arose in response to a disenchantment with the rational world. In short, Dionysus had all the trimmings of the kind of counter-image that Donald Duck had initially embodied for him.

Pamela Kort, external curator of the exhibition "Markus Lüpertz. Über die Kunst zum Bild (Toward the Image through Art)" - on view until 27.01.20 at Haus der Kunst zu sehen. This essay is an excerpt of the exhibition catalogue.